Guest contributor, Dr. Maung Zarni

For my fellow democrats from Myanmar, wherever they are, I have bad news. It is this: the United States (that is, the U.S. government) is not our friend in our uphill struggle for our basic human rights and democratic freedoms. As someone who was educated in the U.S., cut my political teeth as a grassroots activist and lived and worked there for 17 years, I have known this ugly fact for several decades. Washington talks the talk of democracy, human rights and freedom, but it typically fails to walk the talk.

This absence of genuine support and solidarity for our pro-democracy Burmese opposition on the part of U.S. policymakers – not simply the hypocrisy of their government as a whole – was one of the principal reasons I ended my exile in the U.S. after 17 years (the other is its illegal and immoral second invasion of Iraq, accompanied by numerous war crimes during the U.S. occupation of that devastated society, on the bogus twin-pretext of Saddam's non-existent WMD and advancing "freedom and democracy" for Iraqi people).

Completely enamoured with the rhetoric of the U.S. as "the land of the free," I went to there as a young student in my twenties, one month before the '8888 Uprising'. But by the second invasion of Iraq, my youthful illusions of "democracy in America" (and by extension) its support for global democratic movement were irreversibly shattered. As a matter of fact, I was cautioned against my rose-tinted view of the U.S. as a bastion of global democracy by my close friend's father the late Dr. Tin Maung Aye. In his capacity as the Superintendent of Rangoon General Hospital, he buried the fourth year Engineering student Ko Phone Maw, the first casualty of the 1988 pro-democracy uprising.

"You need to get rid of your jaundiced view of the USA and the West", were his perceptive words he uttered when I paid him a goodbye visit to his official residence in Rangoon a few days before I flew out to San Francisco. During my years as a grassroots organizer, first as a student activist and later as a start-up academic, I was intimately involved in and interacted with so many different American institutions and individuals who led or staffed them, from city councils, state legislatures, churches and student organizations all across the vast sub-continental country to the White House, U.S. State Department, Congress, U.S. government funding agencies (such as the U.S. Institute for Peace and the National Endowment for Democracy), and numerous think tanks of all ideological stripes and colours. There were so many wonderful Americans who cared, and who wanted to do the right thing – support democratic movements around the world.

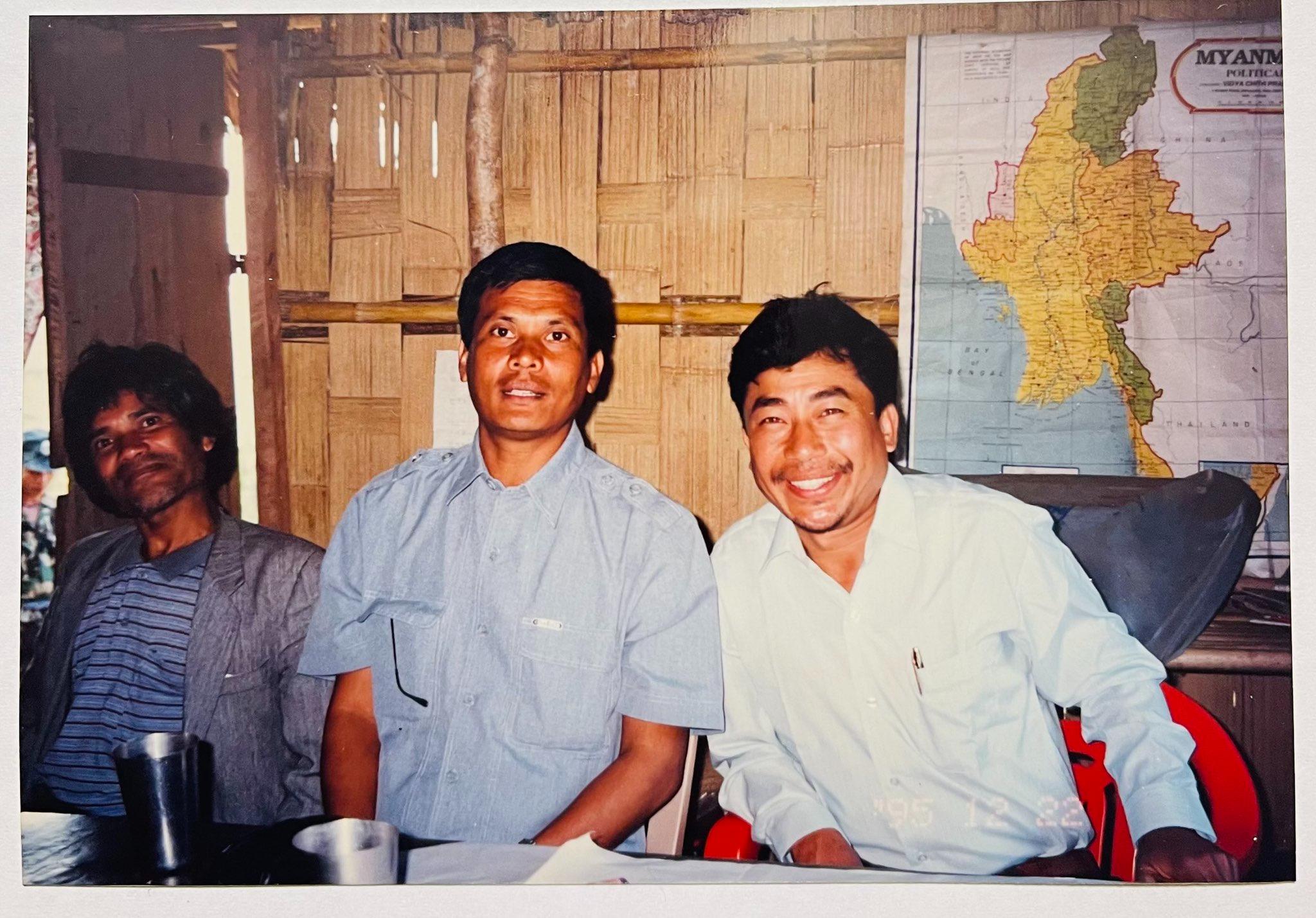

My old Free Burma Coalition colleague Naw May Oo, another American-educated refugee who now advises the Karen National Union (KNU) and I were fortunate enough to have met some of the straight-talking Americans who were part of Washington's Burma policy circles. They gave us an equivalent of a shock therapy when they told us very bluntly, out of appreciation for our committed activism. A few individuals deserve a mention for their honesty. Right after the infamous 2003 Depayin massacre during which the NLD leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her deputy U Tin Oo escaped the botched assassination, we met at a Senate office with the two key aides to the Chair and Ranking member of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Senators Richard Lugar (Republican, Indiana) and John Kerry (Democrat, Massachusetts) to see if there could be stronger support for the flagship NLD opposition in the heartlands and the ethnic armed organizations in the conflict zones.

Their response? One said to us, "If Aung San Suu Kyi were assassinated by the junta [Burmese democrats] would get a statement of condemnation from the United States government." Another chimed in, "You might also get a memorial service at the National Cathedral." [Given Aung San Suu Kyi's moral standing in the world today – because of her ignominious defence of the indefensible (the Rohingya genocide) at the International Court of Justice, even a memorial service in honour of the 77-year old Lady in captivity seems inconceivable.] Matthew P. Daley, a former Korean War vet who was then Deputy Assistant Secretary of State in the East Asia Bureau within the State Department was far more specific and blunt. In our one-on-one conversation, he said, "I can't conscience my government's empty pro-democracy rhetoric. But in reality, we let pro-democracy dissidents mowed down by authoritarian regimes."

He gave an example of the crushed Hungarian uprisings against the Soviet-backed regime in Budapest during the Eisenhower presidency in 1956. Over 20,000 Hungarian democratic activists were slaughtered, and Washington's support, which was never intended to be real, well, never came. He recounted in his meetings with the Chinese counterparts in Beijing, how he dropped the official script of Washington's pro-democracy concerns for Burma, in hopes that the Chinese Communist Party leadership may get the message that the giant neighbour had nothing to fear of U.S. backing for the Burmese democratic opposition. For there was no such thing! Since the Hungarian uprisings, there have been too many cases of pro-democratic and pro-Western movements and governments, that Washington has abandoned. Among them were Burma's neighbours, namely South Vietnam and Cambodia. The latest was Afghanistan falling back under the Taliban. Abandoned by their American allies in power, pro-American democrats in Saigon in the 1970's and Kabul in 2020, desperately trying to get on the last U.S. transport aircrafts, has now become a gut-wrenching iconic image in 'socio' media and on TV screens.

Alas, such warmth, honesty and solidarity don't extend beyond individual officials. You may be friends with U.S. officials. But their government is not a friend of your struggle. That is, unless supporting your resistance advances America's core interests, ala Ukraine. This was a rude awakening for me personally, which in turn compelled me to seek an alternative of finding ways to reconcile with the oppressive military leadership. In the absence of real support from the U.S. in particular and the liberal West in general, I sought to explore ways to help end the country's vicious cycle of violence and counter-violence, repression and resistance. My efforts came to nothing. Now I feel I am back to where I started some 20 years ago when I split with Aung San Suu Kyi-led flagship opposition movement and advocated the stance, "we must talk to the generals".

I knew that Washington would sell us, democrats, down the river. Then President Barack Obama and his Secretary of State Hilary Clinton went to Aung San Suu Kyi's fabled colonial mansion in Rangoon, with global publicity and fanfare, but they removed her only leverage, namely financial sanctions against her military captors. According to Obama's National Security Adviser Ben Rhodes, in her meeting with the U.S. President at the Oval Office in 2013, the Burmese opposition leader did ask Obama to retain financial sanctions. She wanted to use them as bargaining chips in her dealings with the generals. But beholden to the interests of American corporations, Obama offered Suu Kyi an all-or-nothing option. U.S. businesses could not wait to enter Burma as the virgin economy where the Chinese, Singaporean, Thais, Malaysians, South Koreans and Taiwanese had already built toeholds during the years of sanctions.

To labour the obvious, the world's most powerful government would do anything to pursue its core interests – not values. Since its founding as a white settler colony, the U.S. has, according to the Congressional Research Services studies, waged over 300 wars and invasions, declared and undeclared wars, "legal" (that is, UN Security Council-authorized) and illegal invasions, covert and overt, sanctions or lifting them, at their convenience. There just isn't significant enough U.S. interests insofar as Myanmar for Washington to really support the Burmese democratic resistance – most violent, widespread and unprecedented in history – which sprang up organically in virtually all ethnic communities and in different social classes.

Two years since the universally opposed military coup of February 2021, the U.S. has only offered the nationwide democratic resistance, made up of Generation Z fighters and several major ethnic resistance organizations (for instance, the Karen National Union, Chin National Front, and Karenni Progressive People's Party) "notional" support, to use former U.S. Ambassador to Burma Scot Marciel's adjective. In the face of 3,000 deaths and 20,000 arrests of Burmese resisters since the violent crackdown of nationwide peaceful protests began, all that the U.S., both Congress and the Biden Administration could do is the provision of "non-lethal assistance" and humanitarian assistance, in addition to a mix of empty statements of condemnation of this or that misdeed by the junta, and dribble of economic sanctions against a handful of Burmese businessmen and entities tied to the junta.

Typically, U.S. officials such as Derek Cholet holds up photo ops with the leaders of the National Unity Government (NUG) and well-timed and well-publicized visits to its "Information Office" in Washington as Exhibit A of the American support. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the reactive "unity of the West" in support of Ukrainian people's defence for their democratic rights have stripped bare Washington's pro-democracy rhetoric. The day NUG "Foreign Minister" Zin Mar Aung had a photo-op with British Foreign Secretary James Cleverly at the British Foreign Ministry in London, Washington's proxy-in-chief Zalensky addressed the British Parliament and openly demanded – I repeat demanded, not requested – fighter jets and more weapons.

Some 25 years ago, I met James Woosley, former CIA director and a staunch proponent of the regime change in Bagdad, at a close American friend's book launch party in Washington, DC. I asked the spook for his advice on the subject of removing the Burmese dictatorship "back home." He exclaimed, "you need a lot of money!". And the man knew what he was talking about. No resistance or regime change could be undertaken on empty stomach or with poor arms. Within seven days of Myanmar coup two years ago, President Joe Biden was seen on live TV news, talking tough against the Burmese coup regime while proceeding to announce his executive decision to freeze US$1 billion that belongs to Myanmar state (that is, people) as a first step towards supporting Myanmar's pro-democracy movement. Like Woosley, Biden, who routinely voted funding Israel, the largest recipient of U.S. military assistance, for 30 years and supported the invasions of Iraq by the two Bush presidencies, too knows very well how costly war and resistance financing is.

And yet Biden refuses to release that $1 billion to be used for the resistance. The lame excuse from the Americans was that they were safekeeping the money for rebuilding Burma as a federal democracy. But without removing the dictatorship no possibility exists for any reconstruction of Burma. Biden's silence and omission of the Burmese resistance speaks volumes. In Biden's remarks at the Summit for Democracy Virtual Plenary on Democracy Delivering on Global Challenges" delivered in Washington on March 29, Biden singled out "the unprecedented unity we've seen from democracies condemning Russia's brutal war of aggression against Ukraine and standing in solidarity with the brave Ukrainian people as they defend their democracy". And yet the man who froze $1 billion USD and, only two years ago, promised more in action to support the Burmese people who too defend their democracy, however flawed, chose not to even make an obligatory mention.

For revolutionary movements to succeed they need friends, particularly "frontline states", that is, neighbours adjacent to the theatres of resistance. To gain support and solidarity from neighbours is of paramount importance, particularly in light of the complete absence of real support from "democracies of the world". Admittedly, none of Burma's neighbours has shown any interest in or will to partner with or recognize the NUG, or support the broader resistance of ethnic resistance organizations and democratic resisters. As democrats we are in-between rock and the hard place. Beijing considers the Burmese resistance – in particular the NUG – as nothing but a semi-proxy propped up by Washington. As democrats and resisters against six decades of a mass-murderous military, we must bang our heads together and rethink the leadership, their orientation, capacities and achievements, against hard, cold odds.

—

Maung Zarni is the co-author of Essays on Myanmar's Genocide of Rohingyas (2012-18). He is a UK-based Burmese exile with over 30-years of first-hand involvement and scholarship in Burma affairs.