Securing justice for the Rohingya genocide

Late last week, Burma announced that its de facto head, Aung San Suu Kyi, will appear before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to defend the country against allegations of genocide. Earlier in the month, in an application filed before the UN's highest court, the Gambia brought charges of mass murder, rape and destruction of communities in the Arakan state, including against the Rohingya people.

The Gambian submission noted that the Burmese state security forces "systematically shot, killed, forcibly disappeared, raped, gang-raped, sexually assaulted, detained, beat and tortured Rohingya civilians and burned down and destroyed Rohingya homes, mosques, madrasas, shops and Qur'ans." The suit asked the court to order Burma to immediately cease and desist from all acts of genocide, to punish those responsible, including senior government functionaries and military officers, and to give reparations to the victims.

The Gambian move comes at a time when influential members of the international community continue to ignore the gravity of the crimes committed and remain busy with their own geopolitical, economic and strategic interests and thus refrain from taking any effective measure to reverse what the Rohingya genocide scholar Maung Zarni terms as Burma's "genocidal project". So far, says Zarni, they had done little "beyond issuing non-binding resolutions and statements of condemnation calling for symbolic accountability measures and ritual repetition of carefully crafted spin of repatriation littered with substance-less adjectives such as 'voluntary, safe, dignified and sustainable.'"

The Rohingya genocide has also brought to the fore the hollowness of the UN Security Council in ensuring global peace and security. The failure of the UN system was palpably demonstrated in the business-as-usual approach adopted by its specialised agencies that seemingly stems from their collective denial of the atrocity crimes committed by the Burmese state against various ethnic groups, including the crime of genocide against the Rohingya.

After having been shunned by the world (in which racism, national chauvinism, corporatism, national security paranoia and Islamophobia reign supreme), the victims of Rohingya genocide are now beginning to feel that the wheels of justice have finally begun to roll, albeit very slowly. In November, along with the Gambian move, two other initiatives appear to have cracked the spell of torpor that had an ominous hold over the international community in the quest for justice for the victims of the Rohingya genocide.

Weeks earlier, in a separate move in Argentina, Rohingya and Latin American human rights groups lodged a lawsuit charging both the military and civilian leaders of Burma. The petition noted that while the military was engaged in murder, gang rape, arson, torture and so on, "the entire genocidal plan… could not have been deployed without the complementation, the coordination, the support or the acquiescence of the different civilian authorities." It targeted Aung San Suu Kyi for overseeing government policies "tending towards the annihilation of the Rohingya", such as confining them to "ghettoes" with severely limited access to healthcare and education. Among others, charges were brought against the Burmese army chief Min Aung Hlaing as well. The complaint sought criminal sanction of the perpetrators and accomplices under the principle of "universal jurisdiction" that upholds that war crimes and crimes against humanity are so horrendous that those cannot be shielded by the garb of state sovereignty and can be tried anywhere.

On November 14, in yet another development on the legal front, the Pre-Trial Chamber III of the International Criminal Court (ICC) authorised the Prosecutor to launch an investigation into the alleged crimes within the ICC's jurisdiction in Bangladesh, where about a million Rohingya refugees have taken shelter. The authorisation came following a request by the Prosecutor to open an investigation into alleged crimes within the ICC's jurisdiction committed against the Rohingya people. The Chamber also received such requests on behalf of hundreds of thousands of alleged victims. It accepted that there exists a reasonable basis to believe that widespread and/or systematic acts of violence may have been committed that could qualify as the crimes against humanity and/or religion against the Rohingya population.

Suu Kyi's apologists—particularly those in the West and in the UN system, who thus far have been peddling the case that "she has little operational control over the military"—appear to have been caught off guard by the announcement of her personal involvement in the Gambia case. In all likelihood, the ICC Chamber Judge's decision and the Argentinian lawsuit have been upsetting for them. Without a doubt, Suu Kyi's decision to own up and publicly defend the dastardly acts of the Burmese security forces (which the UN Independent Fact-Finding Mission noted as "genocidal" constituting "crimes against humanity") only corroborate the fact that despite her differences with the military on the scale and pace of reform in Burma, there has been no discernible distinction in their methods in dealing with the Rohingya.

As of now, neither in words nor in deeds has Suu Kyi given any indication of her displeasure, let alone disapproval, with regard to the genocidal acts of the Burmese military. On the contrary, she had no hesitation in branding the victims of genocide as "terrorists" and blaming those championing the Rohingya cause for generating "icebergs of misinformation". Her administration resolutely rejects repeated calls for independent investigations into the allegations of atrocities against the Rohingya and their access to the Arakan region. It persistently denies requests for visits by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights on Burma and the Independent Fact-Finding Mission.

Quite like "the emperor's new clothes", the National League for Democracy's excitement about what it perceives to be the State Counsellor's bold decision "to face the lawsuit by herself" lays bare that the fallen angel had all along been in absolute cahoots with the murderous generals of Burma.

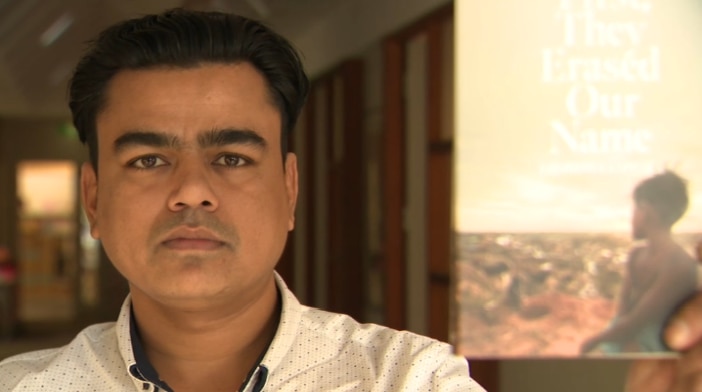

CR Abrar is an academic and rights worker with an interest in refugees, migrants and the stateless.